WORDS: Jill Andresevic PHOTOGRAPHY: Julien Roubinet

There is an in-between space that every maker knows. The space between falling and flying. To fall is to give yourself up to someone else’s vision. To fly? Doing whatever it takes to see your vision come to life. Any vision worth having is formed by fire, grit and determination. Unsurprisingly this is the story of Sean Yoro.

When he was 22, Sean moved from Hawaii to New York City to become an artist. Once in the city, he worked multiple jobs to make ends meet. Living in a cramped painting studio without a shower, or a kitchen, it finally came to Sean how to make his mark as an artist. He always loved street art, and he loved water. And because he hadn’t seen anyone dare to bring art to elusive locations only accessible by water, Sean decided he’d be the first. He didn’t know how Brooklyn or the city worked, but he knew the ocean. It was his comfort zone, a place where he could experiment and do his own thing. That’s all he needed.

He found non-toxic paints that were made with natural pigments, invested in a stable paddle board, scouted locations: walls and other structures accessible only by water, in and around New York. Over 5 months he executed ten test paintings, of which six failed. He photographed the four that worked, posted them on social media on a Wednesday. And as luck and timing would have it, by Friday CNN and The Guardian were calling him for interviews.

What seemed like overnight success took four years from the time Sean landed in New York City to completing his first water mural. His fortitude and desire to create works of art that leave an impact and ignite a sense of urgency around climate change have been well-documented. When interviewed by a reporter about the rapidly melting icebergs that Sean uses as a canvas for both artistic and political reasons, Sean said “humans don’t respond unless we actually see the danger.” Through his art, Sean visually and viscerally reaffirms the need to respect and protect nature.

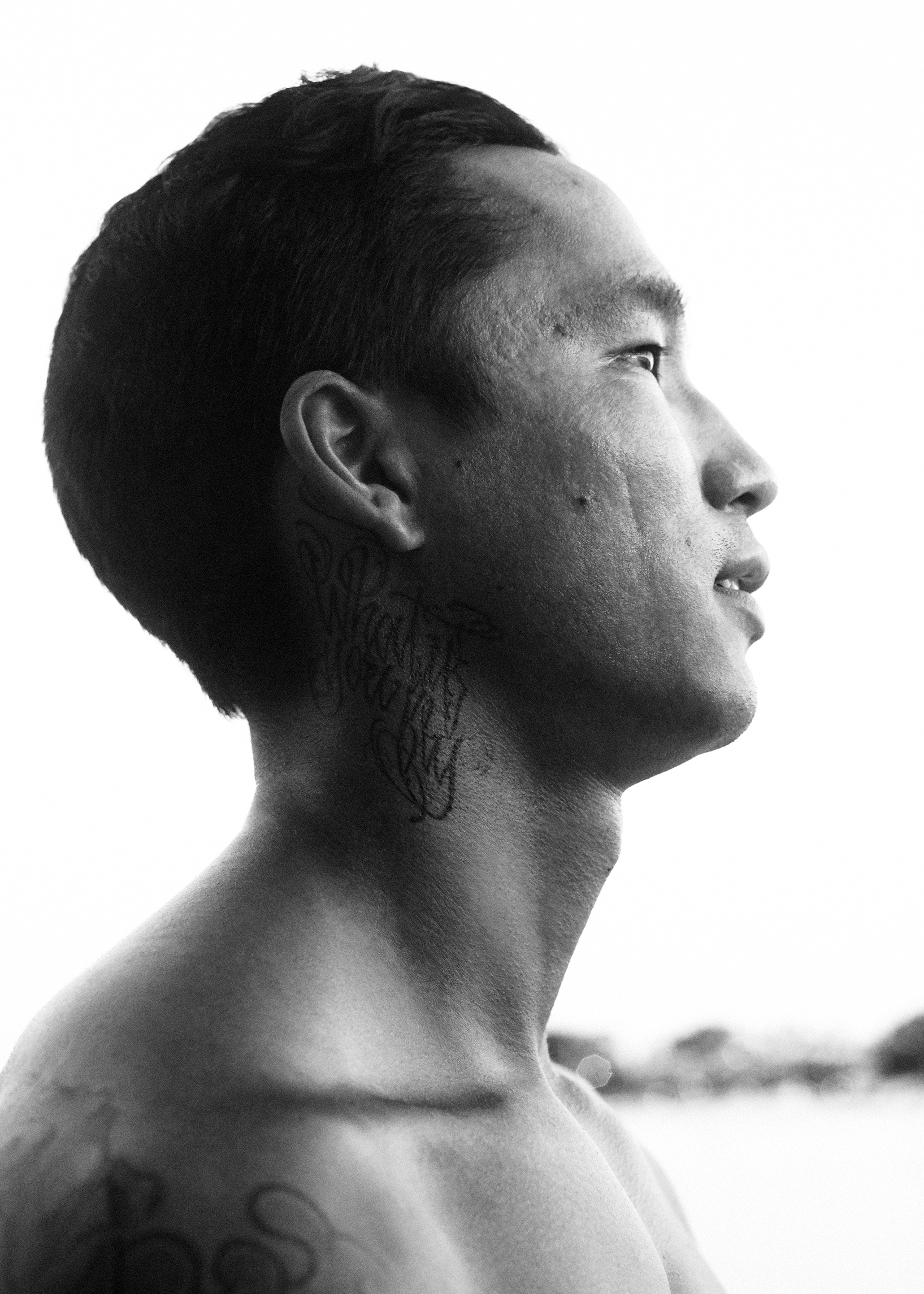

Reflecting on my time with Sean, it makes sense that the tattoos most important to him are the ones behind his left and right ear. “What if I fall?” on the left. “What if I fly?” on the right. From the very beginning of his journey as an artist Sean knew that to fly, he must have courage, which is not the lack of fear, it is the willingness to embrace it. I met with him in Long Beach, CA where we paddle-boarded out to one his murals, talked about the first time he painted a large scale mural on ice, and the space we sometimes all find ourselves—between falling and flying.

What was the first thing that you remember making?

I did a series of one minute sketches with live models, on toned paper in black and white. It was for a figure drawing class at a community college in Hawaii, where we studied anatomy. They’re called gestural drawings, a very preliminary sketch. You keep it abstract to the point where you just get the gist of what the body is doing - the pose, the proportions, the angles. You have one minute to do three or four gesture drawings. I would spend hours doing these. It was one of the first things I loved to do.

At the time, I was doing a lot of surfing, trying to be a lifeguard. But once I get obsessed with things, I get into this tunnel vision mode. I said to myself, "All right, New York is the place for art. Let’s naively jump up there for a year or two." I ended up staying five years. But I'm glad I did. If I knew how much work it was actually going to be, I probably would have stayed in Hawaii.

Why do you do what you do?

I want to tell stories through murals that raise awareness on subjects like climate change and social issues. I want to beautify the city and give people who don’t have a voice the platform to speak about the issues they care about. I grew up with a lot of talented graffiti artists in Hawaii. I always respected them and loved what they did. I always had it in the back of my mind that I wanted to paint on huge walls. In New York I was going crazy and surfing kept me stable, so I made my way back to the ocean, where I could experiment and do my own thing.

I'm always testing new things and innovating different tools. Every project I do never has the same variables. I remember making these big, homemade, three-foot chunks of ice in my bathtub in the middle of winter in New York one. Friends would come over and ask, "What are you doing?" And I’d just say, "It's for a project." If I wasn't a painter, I'd be some kind of inventor because I love designing new things and seeing how things work.

What's your process?

I go out and explore remote places and take a ton of pictures. I look at what I can play with, the specific physical aspects. There has to be a smooth wall and I have to be able to prime it. Then I go back and scroll through the pictures and work with initial sketches. I always base the painting off the location. I'll usually sit on it for a week or two, then work through it again to see if everything translates well. Once I know that I want to paint there, I’ll go into the logistics of getting a team and executing it. I like to do organic photo shoots of my subjects in my studio to see what looks best; and to also see what vibes I’m getting from them.

Recently I did an expedition to Baffin Island where I painted a local Inuit woman on ice. We met up with Jesse in her home town and I deeply connected with her, which created deeper layers of meaning in the mural. There's all these intricate things that influence the final piece through interacting with the subject. It was like capturing that whole trip in one painting. We had a film crew up there that documented it —Camp4Collective and directors Renan Ozturk and Taylor Rees. It was a really cool story. I loved the experience of it.

Why do you paint on icebergs?

The first time I painted on ice was in Iceland. It was a passion project to raise awareness for climate change. I had this crazy idea to go paint on melting icebergs and have these figures melt into the ocean. It was the trickiest thing I've ever done. There were so many different variables to deal with—going that far off the grid, camping, scouting these spots, finding the right iceberg.

I was fortunate to have a good team that came with me to make sure things ran as smooth as they could. I didn't realize how fast the icebergs were melting, especially during summertime. A lot of them were cracking, splitting off, and flipping over. I had to paint and get out of there as quickly as possible. Icebergs move fast. We'd paddle out, find an iceberg, grab the paint and all the gear. By the time we’d come back, the iceberg would be a mile down. We had to time the tides coming in and out. I anchored myself to the iceberg with these long screws that mounted me to the ice itself and painted for nine hours straight while it was moving.

There were a couple of times where I got squished up against two icebergs. I had to wiggle my way free and then wait for it to float away. We had safety equipment, but it was a good six hours to the nearest hospital. If that thing would have flipped over, I was anchored in. You can't control these things. It took a lot of work and a ton of research. I wore a wetsuit on top of layered clothes. We had a ton of rain gear and huge gloves. The gloves made it difficult to paint. Oil paint works differently when it's in a cold temperature, so I had to layer it differently. People misjudge how much gets put into these murals. They just see the finished piece, they don't see the months of research and scouting that goes into it.

Where does your inspiration come from?

Growing up in Hawaii the ocean is never predictable. As a surfer, you get the most powerful waves and there's no one there but yourself. I love to study the ocean to see how it reacts, so water has always influenced my paintings. I love exploring and I'm inspired by nature.

I also love puzzles and seeing how things work, so the trial and error part of making things is part of my inspiration. There are always variables, you are in the elements, in different environments - you might be against ice. And when it's cold, oil paint works differently, so you have to layer it another way.

In your dark moments, how did you keep things from unraveling or coming apart?

I never wanted to stay at home. I always wanted to go out and paint somewhere else. When I started working on my first series of water murals, I used every free minute I had off from work to paint. Then I would go straight back into the restaurant the next day, super tired.

The lowest moment in New York was living in this little eight by ten studio in an office building. I would shower at a friend's house or at the gym. I didn't have a kitchen so I would eat cans of beans and boiled eggs. It was illegal to live there, so at night they would do inspections once a week or once a month. I would jump up, roll up my sleeping back, and pretend I was working. I lived like that for three years.

If I was sacrificing for myself, I wouldn't have enough drive. Ohana means family in Hawaiian and I have so much support from my family. In Hawaii, my uncles would drop everything if I needed help on a project. My mom has always supported any venture I wanted to go into 110%. She was a single parent pinching pennies just to keep food on the table for me. To have people sacrificing for me drives my work ethic to keep pushing 110% into what I’m doing.

If there was something you wish you knew sooner as a maker, what would it be?

When I first started doing art in New York I thought I had to be a certain way and make high realistic portraits to make money. I thought that’s what galleries wanted. I would calculate everything and expect a return.

Then I decided to let go of what I thought would make money and started to do whatI loved—and that was to work in the water. I poured everything I had, all of my resources, into my first project. It was freeing and I could think clearly. The clarity of not letting everyone else influence what my work should be allowed me to stay in the creative zone to do I wanted.

My whole life had been influenced by art and surfing and I combined everything into one. I felt like it was my responsibility to do these murals. I never expected to make a living off of it. When I completed my first water series, it was fulfilling and I didn't care if it took off or not. Of course I was happier when it did. But everything came into place at that time in my life.

What’s the last thing you made?

A portrait of a figure staring off into the depths of the ocean. I wanted to accentuate this waterway in Long Beach. Ferries will be able to see it as they're going out of town. This is a painting of my girlfriend, Melissa. We met when she was working for a gallery in New York, now she lives here.

The mural took four days, and about three gallons of oil paint with high quality pigment. It will start to fade in six months; though this one doesn't get that much sun, so maybe a year or two.

This is a largest scale painting I've ever completed on water. It’s a good ten feet bigger than I usually work with. We had three levels of scaffolding on a little barge almost the full width of the pylon. The first day we came out, the scaffolding almost fell into the water. It was definitely a challenge to get all the way up there and paint steadily. I had to time my brush strokes with every ripple the water, waiting patiently for the perfect moment to paint.

What have your water murals taught you about yourselves and others?

It’s taught me I'd rather think big and fail than think small and succeed. I have self-doubt. With every project, I feel like I've gotten in over my head with what I want to do. It's always a battle with myself but it’s about taking that risk. I love those flying moments when you actually succeed in pushing the limits and pulling something off that has never been done before.

Iceland was one of the craziest expeditions I've been on and it started with a doodle in my sketchbook. On the fifth day nothing was going well. It was freezing and we were out in the middle of nowhere trying to find an iceberg. It only came together the last day we were there.

After that trip I got these tattoos. They say, "What if I fall?" and, "What if you fly?" It's like the devil and the angel on your shoulder which is why I got them behind each ear. Which one do you listen to? Fall or fly?

MakersFinders is a digital platform that connects independent makers to passionate finders.

We have an app in private beta. We publish stories. We host events. And provide quarterly grants for our community of Makers and Finders.

Our team is dedicated to cultivating and connecting communities across various industries and cultures.