WORDS: Yahdon Israel PHOTOGRAPHY: Julien Roubinet

The American writer, Susan Sontag, believed that photographs were capable of shocking us if they could show us something new. But when looking for the novel, the question almost immediately becomes how do you find something you've never seen before? Do you actively pursue the new? Or do you allow yourself to be discovered by it? For London born, Brooklyn based, photographer John Midgley it's been both. Discovery is a simultaneous act of looking and being lost. Sometimes we find what we're looking for. But so many other times, what we're looking for finds us.

This is how John explains the gift that has been his 30 year photography career. A great deal of it was spent in the pursuit of the unknown; an even greater deal was trusting that the pursuit was worth it. And in John's case, it has been. Photographing everyone from Harrison Ford to Mos Def, John has learned that showing people something new isn't necessarily about creating what isn't there; it's merely an act of capturing what you see.

I met John at his studio in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn where we talked about the radio transmitter he made out of Legos to communicate with aliens when he was seven; how he reconciles his creative and commercial impulses; how our memory can sometimes fail us; and why art will always be more about the journey than the destination.

What was the first thing you remember making?

A Lego radio transmitter I used to talk to people in outer space. I was convinced that I could hear people. I was maybe seven or eight. I wanted to talk to aliens.

I could remember imagining hearing stuff, like static. There was some communication going on. My mother, who studied as an occupational therapist, was into art as experimentation—and art as expression so she understood what I doing.

Why do you make what you make?

I always felt that emotions, feelings and thoughts were visual. So photography just clicked for me.

I never thought that’s what I wanted to do as a profession but once I started doing it I thought, “Oh this makes sense.”

Do you see photography as a way to articulate or gain access to your dreams?

There’s two sides. One is making money, paying rent, having a nice lifestyle—and everything that goes with that. On the commercial side you’ve got someone who wants something. They want a picture to look a certain way and it’s your job to achieve that. Part of the challenge is figuring out what it is that your client wants.

It’s all very subconscious and it’s hidden. You don’t always know why you want something. You wake up and you’re like “What was that about?” Whereas your subconscious knows exactly what that was about and it’s trying to communicate the meaning to you and you’re just trying make sense of it.

On the artistic side, photography is chasing the subconscious and trying to connect to it.

Does your approach to photography change when it’s creative versus commercial?

When you’re doing artistic work you don’t know what the end product is going to be. It’s like you’re fishing. You don’t know the type of fish you’re going to catch; or if you’re going to catch a fish at all.

I did this series where I was just walking and taking pictures. The whole time. I wasn't even looking. That series was exactly that process of not knowing what I was going to get. You’re searching but not you’re not conscious where. Then when you get the film, you start to edit and build up a story. Like Lego. That's when the images begin to resonate and you begin to get a feeling for what the story is about, and it’s never linear. It’s not about creating what isn’t there; it’s about capturing what you see.

Commercial work is constructionism. You know what it is. You know what you’re doing. There’s the unconscious part where you’re trying to figure out what the client really wants but this is something you get with experience. You begin to know the parameters.

If there was something you wished you would’ve known sooner, what would it be?

On the commercial side, I feel like I learned a lot more. The one thing I really learned is if you’re making money, that’s what you’re doing. It seems very obvious but where I come from, your work is an extension of yourself and you shouldn’t compromise. Ever—and that was my attitude: “I don’t care how much this job is paying. I’m not going to shoot that.”

At a certain point—especially during the 2008 recession—there was no money coming in. I have the kids, the mortgage. When there’s nothing on the table it’s really scary. And there’s no trust funds. There’s no family members who can float you. You’re on your own. You’re on this little boat at sea and someone’s taken the oars and the sails away—then you’re like, “Ok, you arrogant bastard, you could’ve said yes to those jobs.” So my approach has been: as long as they’re paying and as long as I can make a good product for them, why not?

What was one of your most meaningful projects?

I did this series called, “Memory.” It was very personal. I used my eldest son as a model. The idea was, when you’re a small child remembering your mother, you don’t really have a tight grasp on the concept of age. And you really don’t get that type of perspective until you’re the age your mother was when she had you.

When you reach that age you realize that your mother being 27, for example, has a significance beyond a number. You realize that your mother was doing the same kind of floundering that you’re probably doing now. She didn’t have all the answers. She didn’t know everything.

So I had my son on the beach where I grew up in England. He was naked—to represent the vulnerability of memories. This older woman is holding his hand. And there’s a younger woman who’s reaching for his other hand. That’s this idea of how conflicted our memories are. You thought you had this really old mother but when you look back she wasn’t old at all.

Who or what are your inspirations?

Susan Sontag's On Photography. You can read that book ten times over and get something new. The worst part of my education was we had to read them. At first I was very standoffish towards it. But the more I read it, the more it became poetry.

Then there’s the personal inspiration like my two oldest sons who are in college. It’s kind of scary and exciting watching them go through everything that I went through when I was their age. Watching them struggle and making decisions, that’s inspiring. You think because they're your kids you can help them and they’ll be fine but you sort of have to stand back and let them find their way.

What was the last thing you made?

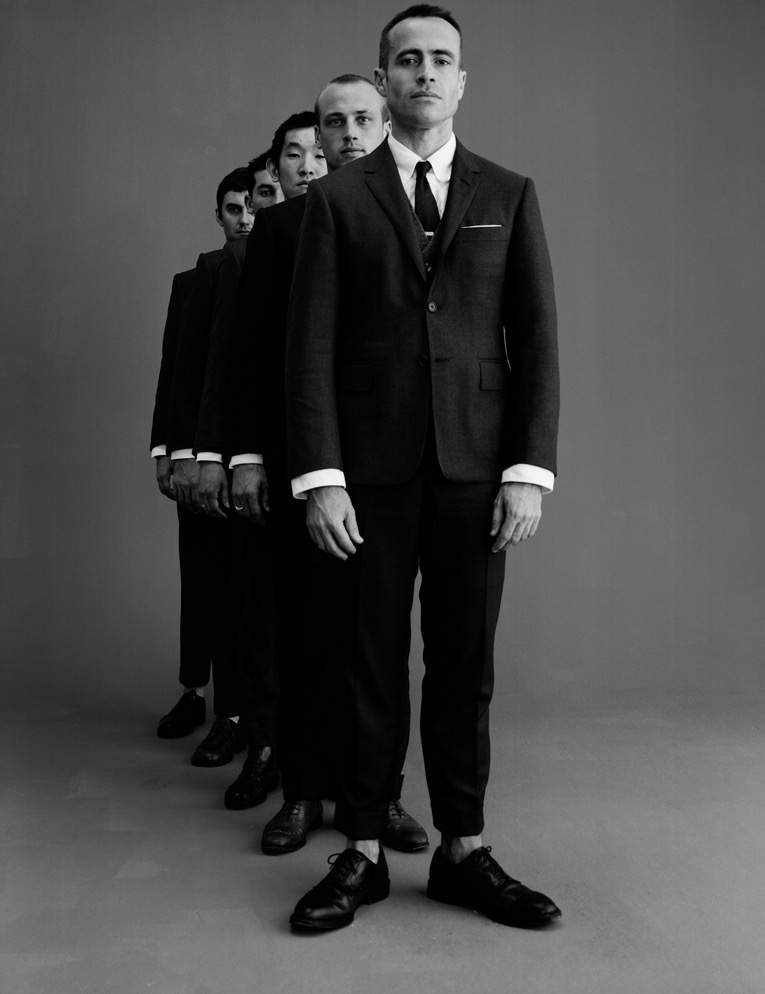

A series of portraits of the people at Liberty Fairs in Las Vegas.

What has photography taught you about yourself and others?

What I’ve realized about myself is I like people and I’m always interested in their stories. I’m always asking questions because I have to build the picture of who a person is as I’m taking it. And depending on who it is, like a celebrity, you only get 15 minutes. They walk in and walk out. So sometimes you have to create that image quickly.

When you’re behind a camera, you get a real range of people—from celebrities to everyday people. And what I’ve learned about people is it doesn’t matter how rich, how powerful, or how famous you are, all of that changes when you’re in front of a camera. There’s rich and powerful people who will shrink in front of the camera; there’s poor people who come alive. You just never know.

After thirty years of doing this, what keeps you going?

My wife Eva and her support. We're always discussing ideas and strategizing about the future together. We are a team.

What also keeps me going is naïveté. It’s like all art—if you know what everything’s going to be every time you do it, why would you do it? The journey is the art. You start with an idea and end up somewhere. The journey from beginning concept to final product, that’s what it’s all about.

About MakersFinders

MakersFinders is a social platform that helps people share what they make and find what they love.

We have an app in private beta. We publish stories. We host events. And provide quarterly grants for our community of Makers and Finders.