WORDS: Yahdon Israel PHOTOGRAPHY: Julien Roubinet

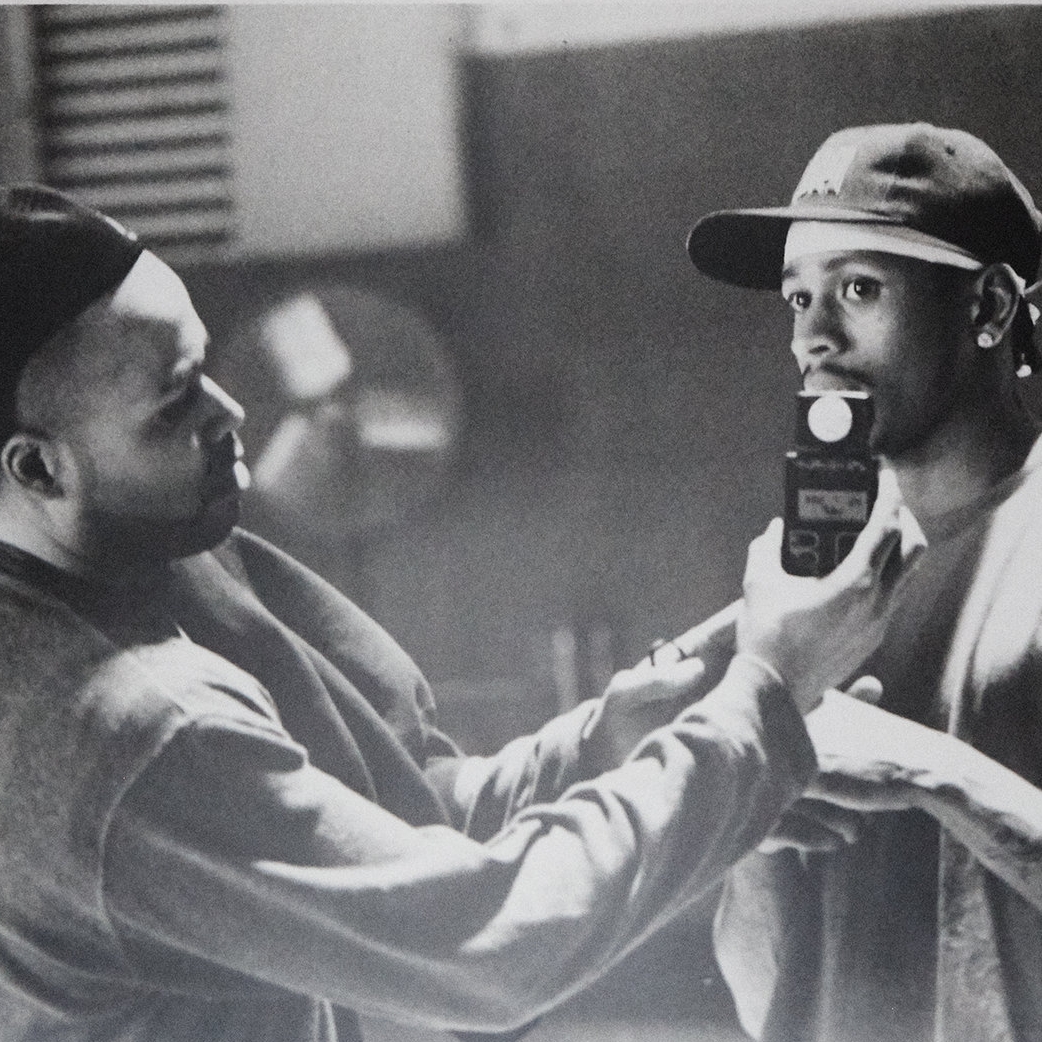

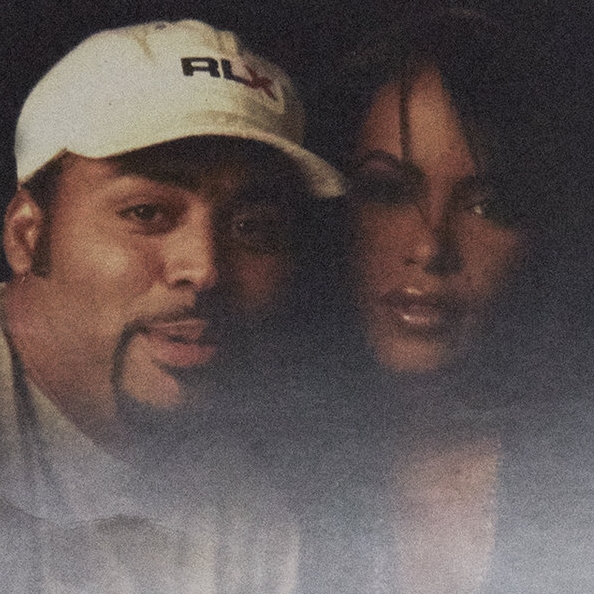

On the computer desk of accomplished music video director Lenny Bass, there rests a box of photographs—resembling trading cards in size and significance—from his days as a lighting director. In one, Laurence Fishburne seems to be caught in between takes on the set of King of New York. In another Slick Rick is captured in his signature Kangol, gold rope and eye-patch leaning against a Kid Capri poster. A young 50 Cent mean mugs for the camera several pictures later. Then there’s one with Jay Z, sitting calm, cool, and all too collected, on a Bedford-Stuyvesant stoop. The more I shuffled through the photos, the more I felt my appreciation growing for the person behind the camera.

What's always intrigued me about photographs is their ability to say as much about the person, taking the picture, as whatever's caught within its gaze. If not as much: more. One after another Lenny's photographs say the things that anyone who has this much history wants to but can't. Not because they're inarticulate. Quite the contrary. It's partially because, if pictures are worth all the words we've claimed them to be, there's not enough time in the day to say all the things that need to be said. Not to mention: the work speaks for itself.

Neither one of these facts prevents Lenny from trying. And in his admirible capacity to not only try and say everything he needs to say while challenging himself to find the words which best elucidate the way he thinks and moves about the world, it becomes crystal clear how Lenny, a Staten Island native, went from not thinking it was possible to go to school for art [Lenny attended FIT for a year before finishing his degree at the College of Staten Island] to provide innovative and instructive ways to see sound.

With director credits that include Nappy Roots ("Aww Naw" and "Round' the Globe"), De La Soul ("Get Away"), Yung Joc ("It's Going Down") Fantasia ("When I See You"), Craig David ("Walking Away"), Elle Varner ("I Don't Care"), DJ Webstar & Young B ("Chicken Noodle Soup"), and most recently: St. Paul and the Broken Bones ("All I Ever Wonder"), what you see in Lenny's work is a sincere belief that even in the most impossible scenarios, there's still possibility.

We met up with Lenny at his home in Kensington, Brooklyn, where, in addition to educating us about the U-Men and impressing us with his legendary collection of photographs, we spoke about how he's continually evolving his craft, even after 20+ years in the industry; the importance of bearing witness to the times we live and why, even in the midst of others, we still have to eventually focus on ourselves.

What was the first thing you remember making?

There was a store named Oak Tree that made this line called the U-Men. I loved what they were doing with the collars and pants and I was trying to get into design, so I'd sketch them.

I was about 16 years old, going to New Dorp High School in Staten Island, taking illustration at this time. My art teacher saw my sketches, told me I had a really good eye for drawing, and that I should consider going to the Fashion Institute of Technology, here in New York.

I always thought you went to college to be a dentist, doctor, or a lawyer. Something "practical." I didn't think you could go to school for art. So I couldn't wrap my head around what my art teacher was saying then. Ironically enough, I was playing basketball around this time and FIT happened to be one of the schools that courted me to play for them. I ended up playing ball there. So when I came back to visit my high school to tell my old art teacher I was over at FIT, she was blown away! But everything began with these U-Men sketches.

Why do you do what you do?

I think it has a lot to do with music. In a strange way directors are this hybrid. We're filmmakers, but we're also the music industry people. I'm inspired by music, and it feels like it's the vehicle to be connected to the song—and to the artist. It feels like I've been fortunate enough to land a few projects where I really, really, really love what the artist is about and the music they create. To get there visually, it's a beautiful thing to be connected for that brief time.

Where do you get your inspirations from?

I get inspiration from everywhere. Have you ever had that everything happens for a reason, no such thing as coincidence moment? I had one of those moments when Atlantic Records sent me Craig David's "Walking Away." What the record labels do is send about ten directors a song and it's our job to pitch them an idea for the video. The pitch the label feel best aligns with the music and the vision gets the job.

My brother-in-law had given me Oscar Scott Card's The Tales of Alvin Maker book series to read around this time. It's this interesting story about how the forces of nature keep trying to kill this guy. Everyone's born with a special ability, and they knew early on that there was something about this kid that nature wanted to kill him. He couldn't go near water. All this stuff.

All of a sudden I began thinking about the connection between this Craig David song and the books. In the chorus Craig David sings, "I'm walking away from all the problems in my life." I wondered what it would be like for him to always be two steps ahead of catastrophe? So in the video we had Craig literally walk away from the problems of his life. You see him put a pot down to catch the water from his leaking ceiling before he leaves his apartment. Almost as soon as he leaves, the ceiling comes down. Then he gets in his car and someone mistakenly throws a match in his back seat. So he's driving completely unaware that his car's on fire. The whole video is about this underlying tension that exists in our lives, and what we decide to do with it. Do we stay? Or do we do what Craig David says and "Walk Away?" I feel that the universe constantly puts things in our lives to remind us that everything is connected in some way. This video was an instance of my paying attention.

What's your process when you approach a project?

My process was always about coming up with something creative then flipping it on its ass. To say, "This is a really interesting approach to the storyline. Now, what are they not expecting?"

There was this moment where record labels were really influenced by the ending of Usual Suspects, where you find out Kevin Spacey is not a dim-witted cripple but the mastermind behind an entire criminal enterprise. After that, every label wanted a twist. I'm sure a lot of us directors were home with our pitches struggling to come up with one. There were many grueling nights trying to find that creative thing that was gonna be the show stopper and how to make that thing palatable for the record labels and artists.

It feels like things have moved away from the unexpected, in a gimmicky sense, and we're at this place where it's more about what's going on socially. I've been fortunate enough to work on a piece with Gwen Carr, who's Eric Garner's mother—[the black man from Staten Island whose last words were "I can't breathe!" due to a chokehold applied by a police officer]. There's a different reward to these projects. Instead of banging my head against the wall, attempting to figure out a way to twist a narrative, I can use my lens to bear witness to what's right in front of us.

How did you make that transition from looking for the twist in every ending to working on projects that proximate us to the social issues of everyday reality? What made you say to yourself, "This is what I'm gonna lend my voice to"?

I'll be honest: a lot of it began with Barack Obama's presidency. Race and racism was always a reality many people faced on a day-to-day basis but over the last four or five years in America these issues have been presented in a way where we have to confront them. Trayvon Martin was a huge turning point. Here's a teenager who's walking down the street with some Skittles and an iced tea, who gets killed, and the guy who kills him is acquitted. That made me start to look a bit deeper into some of the things I previously ignored because these situations are way more nuanced than before. At least to me.

Then this awakening, my awakening, is happening in a time where there's more platforms which allows these issues that always bubbled beneath the surface to actually push through and find their audiences. There weren't as many outlets before. There was no YouTube or Vimeo. Our stuff always had to go to network TV and there were all these rules.

Because of all the content and media platforms, the rules have changed. And that's helped a lot of people see things that are necessary if they want to change for the better. One could only hope. In some ways I still feel a bit confined by how things used to work but I'm slowly stepping into this new space with a reinvigorated vision of what I want to see and what I feel should be seen.

What is something you wish you had known sooner?

I think that there's a right time and a right place for an idea, but I do wish I would have understood who I was as a filmmaker, what my message was, what my voice was, sooner. I was just focused on doing the work. Who knows? Maybe asking these deep questions would have possibly led me to work with more artists that I really, really, respect. I have my handful of artists that I worked with that I love and respect to this day—De La Soul, Jill Scott, Cee Lo, Nappy Roots, Fantasia, Pharaoh Monch, a bunch of them—but I just see that prodding myself about what I wanted my vision to be earlier wouldn't have hurt either.

What do you feel like your craft has taught you about yourself?

To keep a child-like perspective on my creativity. That means allowing myself to dream. Allowing myself to go to those places often misinterpreted as unsophisticated and not be ashamed that I'm there. The minute I turn that off how can I continue to dream?

I used to follow this guru, who I went to see speak on Staten Island once. We're all sitting in the room, in lotus pose, waiting for him. He eventually comes down and sits with us. We didn't even know he was there. We finally opened our eyes and he's sitting there, still meditating. We waited another ten minutes, and he says, "I was in such a peaceful state that it pained me to come out of it."

I tell this story because it does a great job of capturing the eternal struggle of putting yourself into that place of peace, and how hard it can sometimes be to return to a world where you're constantly going up against something to exist. So much of my professional life had been based on someone else telling me when things were and weren't "OK." What could or couldn't be done. And there was always a legitimate anxiety with this as my livelihood was linked to those expectations in very real ways. In many ways it still is but I'm learning how to preserve my moments of peace and insist on giving myself the permission to dream.

What has this approach taught you about people?

It's many different things. One of them is that not everybody is willing to take a chance. I understand that it's not easy for people to be in that childlike space. I remember doing this job with Cee-Lo, and the record label wanted me to turn him into their vision of him.

They were worried about the direction Cee-Lo was taking because he was losing his "urban fans." So during this time, the label was doing a lot to get me to try and get him to wear this brown leather outfit that wasn't him. Long story short he went along with it. He tried it on. He's like, "How's it look?" Everybody's like, "It's great." He got undressed. We went back to talking about the idea for the video, then he left.

Later, I'm in the hotel room and, the phone rings. It's Cee-Lo: "Yo dawg, I just left the mall. I got what we're looking for." I said, "What are you talking about?" He said, "I saw your face, man. I saw your face. I got what we're looking for." I was like, "All right, man."

He walks on set in riding gear with this side saddle pouch, hat, and glasses. The label sees him and run to me. "Cee-Lo's got something on. He can't wear that. You gotta talk him out of that." I go to talk to him and he asks me, "What'd you think [of the outfit]?" I'm like, "It's beautiful." Beautiful. He's like, "All right. That's what I thought."

A little while after that, he was in Gnarls Barkley, where one of the album promotions was of him in a wedding dress. Around this time there was an article about Cee-Lo, where he said that it was the first time he got to be all of him. When you find that thing that allows you to be in your space, and nobody can tell you otherwise, and everything that you do comes from that channel, you're not gonna question it anymore. It's very rare to find people who feel confident in themselves enough to risk everything else. Whatever that may be. That's what I try to do now as much as possible: bring all of me to my creativity. I'm not always successful but I'm always trying.

What's the last thing you made?

I'm making stuff all the time but the last music video I made was for St. Paul & The Broken Bones' "All I Ever Wonder." The hook goes: "I can't tell which side I'm on/I can't tell what's right or wrong." It was an idea that interested me. I can't tell which side I'm on. I can't tell what's right or wrong. I'm fighting for this thing, and this thing could turn out to be possibly bad. The song spoke to me, so I wrote a concept that featured people protesting with signs that were conflicting in messages—Pro-gun/Anti-gun, Pro-Life/Pro-Choice—something with a lot of tension.

The company representing me heard the idea and told me, "You can't do this." So I told them, "Well this is what I'm going to present." "You have an opportunity to get this job," they told me, "and you're throwing it away." I felt like this was a good enough idea for me to lose the job and stood by it. It turned out that the label, artist and management loved it. Very rare.

But then they wanted to make all the protest signs in the video vague. Abstract even. "It should be peace, love, hope, justice." I'm like, "All right. Not as powerful, but cool. Let's do it." I loved the song and felt there was enough to still get a message across. The video ended up being released without most of the tension. People are marching but there wasn't any conflict. Nevertheless, it was a wonderful experience!

"All I Ever Wonder," Edited Version.

"All I Ever Wonder," Director's Cut. Courtesy of Lenny Bass.

What do you feel like you need to continue doing what you do?

You know what it is? It's constantly being inspired. That's going to allow me to continue doing what I'm doing, and create things that I'm really excited about. There's no way you're gonna wake up in the morning and make something that you're proud of if you're not excited about it. Those things that you wake up and you're like, "I can't wait to start."

I heard Diddy say in an interview once: "Some of us have careers, and some of us have jobs." When you have a job, you're looking at the clock, wishing that time would go. When you have a career, there's not enough time in the day—and it's true. And I'm happy to say for me, there's never enough time in a day!

MakersFinders is a digital platform that connects independent makers to passionate finders.

We have an app in private beta. We publish stories. We host events. And provide quarterly grants for our community of Makers and Finders.

Our team is dedicated to cultivating and connecting communities across various industries and cultures.